For thousands of years there was only one all-weather north-south route in eastern Ireland. Every major war fought in this country revolved at some point around Bearnas Bó Uladh, the Gap of the North.

There is an old adage that geography determines history, which is the record of human interaction with a given environment. 20,000 years ago much of Ireland was covered by an ice cap, some of it a kilometer thick. 13,000 years ago, as the great glaciers retreated northward, they dumped vast quantities of accumulated gravel and rock in a line of heaps across Ireland. These are the drumlins, the great belt of little rounded hills that runs from Bangor in Co. Down to Clew Bay in Mayo.

There is an old adage that geography determines history, which is the record of human interaction with a given environment. 20,000 years ago much of Ireland was covered by an ice cap, some of it a kilometer thick. 13,000 years ago, as the great glaciers retreated northward, they dumped vast quantities of accumulated gravel and rock in a line of heaps across Ireland. These are the drumlins, the great belt of little rounded hills that runs from Bangor in Co. Down to Clew Bay in Mayo.

Drumlins make life difficult for roadbuilders, as drivers in Cavan and Monaghan know. They are generally too steep to go over and often too boggy to go around. Even with modern equipment that can cut through them, they are difficult – which is why it took so long to get the Newry bypass even though there was really just one drumlin in the way.

There are two natural breaks in the drumlin belt: Lough Erne in the west, and the hills of South Armagh in the east. Passes through the hills provided an all-weather route that did not flood in winter and could not easily be flooded for defence. In ancient times as today, the wealth, good land and population are mainly to be found in the east, so the eastern road was always of much greater strategic significance.

According to the Annals of the Four Masters, in ancient times there were five roads leading from the five provinces of Ireland to the Royal Seat at Tara. The northern route, known as An Slí Miodhluachra, began at Dunseverick on the Causeway Coast, came from Emain Macha along the eastern slopes of Slieve Gullion and by the Old Road and Ballynamona Road to Carrickbroad, then passed between the hills of Slievenabolea and Claret Rock before descending to the plain of Muirthemhne (red line).

This hill pass is referred to in the Táin Bó Cuailgne as Bearnas Bó Uladh, roughly the cattle-raiding pass of Ulster, but we call it the Gap of the North. At the northern end of the pass, close by Kilnasagart railway bridge, a little river flowing from Slieve Gullion heads south-east for Dundalk Bay. This is what the English armies came to call the Three Mile Water, three Irish miles from Dundalk. In ancient times the river was probably in the middle of a little bog crossed by a path of logs or branches, which we still call a céis. To the extent that the Táin Bó Cuailgne represents actual historical events and real places, it is likely that some of Cúchulain’s feats of arms at fords happened here.

Close by is the Kilnasagart stone: the Christian inscription has been dated to around 700AD but the stone was erected centuries before, possibly as a boundary marker and a sort of warning that there might be a crazy kid down at the céis waiting to lop your head off if you tried to cross. The inscription reads: ‘In loc so Taninmarni Ternoc mac Cernan Bic er cul Peter Apstel’ – this place, Ternoc, son of Ciaran the little, bequeath it under the protection of Apostle Peter. Ternoc is known to have died about 715AD

In the Christian era the route grew in importance since it was the road to the ecclesiastical capital in Armagh. Monasteries made much of their living by providing accommodation for pilgrims and other travellers. It was an easy walk from Faughart to the next monastery at Killeavy: in the 1130s a new monastery in Newry turned the road via Baile an Chlár (later Jonesborough) and Cloghogue (blue line).

Sometimes the terms ‘Gap of the North’ or ‘Moyra Pass’ were used to designate the two kilometers or so from Faughart to Kilnasagart, sometimes for the whole ancient road from Dundalk to Newry. Local people didn’t help, often using Gap of the North to refer to the Gleann Dhu pass on the other side of Carrickbroad mountain, which it must be admitted looks more like a pass as seen in the movies. However, ‘pass’ or ‘pace’ as used by medieval and early modern writers generally referred not to mountain routes but to roads across valleys or more often through woods. In the 1950s the writer H.G. Tempest, whose family owned the Dundalk Democrat, attempted to put an end to the confusion among historians by publishing his own map.

In the 1170s the Norman invaders built a motte or temporary castle at Faughart, probably on top of a Neolithic burial cairn. It would have had a wooden fortification on top like the ones in Braveheart, defended by crossbow archers. Although the Normans seldom had much problem pushing through the Gap, they were unable to hold the land to the north apart from outposts in Carrickfergus, Downpatrick and sometimes Newry.

In 1315 the motte was occupied by Edward Bruce, younger brother of Robert, king of Scotland. Edward had himself crowned king of Ireland in Dundalk a year later, but he ravaged the country so severely that a combined Norman/Irish force confronted him in October near where the Ballymascanlon roundabout now is: the battle raged in the area between the roundabout and railway and back to the slopes of Faughart hill. Bruce was killed in his own camp by an infiltrator dressed as a jester. It is believed the site of the camp is now Liam Rice’s builders yard. His head was pickled in brine and sent to London. Or rather, some head was. According to Sir John Barbour, historian of the Bruce family writing 50 years later:

Ireland in Dundalk a year later, but he ravaged the country so severely that a combined Norman/Irish force confronted him in October near where the Ballymascanlon roundabout now is: the battle raged in the area between the roundabout and railway and back to the slopes of Faughart hill. Bruce was killed in his own camp by an infiltrator dressed as a jester. It is believed the site of the camp is now Liam Rice’s builders yard. His head was pickled in brine and sent to London. Or rather, some head was. According to Sir John Barbour, historian of the Bruce family writing 50 years later:

“Those who were at the fighting looked for Sir Edward to get his head among the folk who lay there dead, and found Gib Harper in his gear; because his arms were so noble, they struck off his head, then had it salted in a box and sent it to England as a present to King Edward. They believed that it was Sir Edward’s but they were deceived about the head by the armour, which was splendid, although Sir Edward died there.”

Nobody knew who they were looking for among the many corpses, what Edward looked like. They beheaded someone wearing his coat with the Bruce coat-of-arms, but the first thing any medieval prince did going into battle was to swap coats with one of his generals, and it looks as if it was Gib Harper’s turn. When the railway came through in 1849, and again when the motorway was built, mass graves were found with skeletons still wearing chain mail.

In the 1340s the English Justiciar or Viceroy, Sir Ralf D’Ufford raided through the pass and deep into the kingdom of Iveagh, raiding the McCartan country when most of the clan was off fighting elsewhere. The McCartan galleys swept into Carlingford Lough: their famous axemen swarmed up through the pass of Annaverna and across Feede Mountain and caught up with the English forces as they approached the Gap. The Annals said D’Ufford lost “his clothes, his money, his vessels of silver and some of his horses: he also lost some of his men”. Like Barbour, D’Ufford referred to the Gap as the Pass of Imermallane (or Innermallan or Emerdullan) but we have no trace of its origins or meaning.

From around that time the English colony in Ireland was seriously weakened by the Black Death. This is the era of the Pale, when a shrunken colony retreated behind a defensive fence (or paling) that ran from Dundalk to Ardee to Kells to Navan to Trim and around Dublin roughly on the line of the M50. One lonely outpost at its northern extreme, Castle Roche, was never in any real danger – the Irish didn’t do castles.

It was only with the Reformation in the mid-16th century that the English regime in Ireland realised that Gaelic Ulster represented a major threat to their power, a base for an attack from the Catholic powers in France or Spain. They were never under greater threat than that from Hugh O’Neill, whom Elizabeth I created Earl of Tyrone. During the Nine Years War (1594-1603) he completely trounced a larger English force at the Yellow Ford near Blackwaterstown in 1596. Elizabeth sent the largest army ever seen in Ireland under her favourite, the Earl of Essex, but he was so tricked and outmanoeuvred by O’Neill that he wasted the army and Elizabeth had him beheaded. The English were so imbued with notions of racial superiority that they learned only slowly to appreciate the skill of the Irish fighting forces, and even to study their methods and copy them. When Elizabeth sent her first army against O’Neill, less than a third of them had firearms. By the end, almost two-thirds had them.

O’Neill’s shock troops were the gallowglasses, traditional warrior communities a bit like the Japanese Samurai who had originally been mercenaries of Norse origin from the Western Isles of Scotland. They had been plying their martial trade in Ireland for 400 years by then, had settled and made their mark on Irish society: the McDonnells and Sweeneys and Gallaghers and McCabes and Doyles and McDowells – and almost anyone whose surname begins with McIl or McEl. They were armoured and wielded claymores or Norse-style battleaxes and they just didn’t surrender.

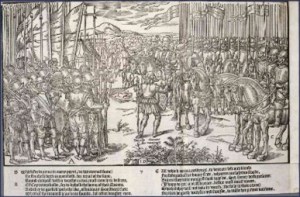

Then there were the kern – ancestors of all the Kearneys – lightly armed and light-footed skirmishers who probably did most of the fighting in Irish warfare. The famous German artist Albecht Durer sketched some of them in Vienna along with two gallowglasses. The sketch was made in 1521: by the time of the Nine Years War some or all of the kern on the right would have been carrying firearms.

After a period of calling them naked, stone-throwing savages the English learned some respect and started to hire them instead. John Derricke’s famous woodcut from 1581 shows them torching English houses in the Pale and driving off the cattle and horses while a piper keeps them in step. To replace Essex, Elizabeth sent the less flamboyant but immeasurably smarter Charles Blount, an Oxzford professor whom she made Lord Mountjoy, in the spring of 1600. In September he set out from Dundalk to bring food and much-needed ammunition to his beleaguered garrison in Newry but he found O’Neill blocking the road through the Gap. Mountjoy had at his disposal a force of some 2400 foot and 300 horse. English estimates, known to be consistently and highly unreliable, put O’Neill’s forces a little higher.

They made camp close to the burying ground on 20th September 1600 and sent out scouts who had to fight their way back to report that the Irish had a number of barricades across the route between the hills of Slievenabolea and Claret Rock. In his journal Mountjoy described his view north from Faughart Hill towards the Moyry as he called the Gap:

‘From the fall of the hill of the Faugher, whereon we lodged … being a little over half mile from the first entrenchment in

the Moyry, there arose northwards two other great mountains or rocks with equal ascent, the one on the right hand [Claret Rock], the other on the left [Slievenabolea], their tops being distant more than two musket shot the one from the other, which were those mountains where they usually showed themselves. In the middest between them lay the way through the woods

of the Moyry, on all sides naturally fenced with stony cliffs and thick bushes and trees’.

.

Mountjoy had a cartographer called Richard Bartlett on his staff who made a series of maps of the battlefield in the Gap and its surrounding area, which was all heavily wooded. The first one shows the road from Faughart hill with the church on top leading towards the Three Mile Water (at Kilnasagart) and on to the Four Mile Water at Flurrybridge. Blocking the way are three ‘barricadoes’ and what may be a trench stretching south-west. Mountjoy’s secretary Fynes Moryson , who was a bit of a war correspondent, says O’Neill ” raised long traverses with huge and high flankers of great stones, mingled with turf and staked on both sides with Palisadoes wattled.” Others describe them as ” great hedges ” or ” a kind of rampire raised upon them with earth and stones and thorn.”

Where the ground rose above the track O’Neill had ” plashed ” the undergrowth and trees, making an almost impenetrable barrier. Plashing consisted of felling trees in a line and driving huge stakes into the ground to prevent them being dragged aside, sometimes also linking them into a barrier with chains. There is a ditch running up Slievenabolea which may well have been built with debris from O’Neill‘s trenches. The English were a bit stunned at the level of fortification achieved by O’Neill, possibly with the help of military engineers from Spain. They were more used to Irish hit-and-run tactics.

Historian Gerard Hayes-McCoy made his own map of the battlefield. The first barricade was at the top of the rise about 300 meters north-east of the Poor Clare Convent, ensuring a nice uphill run for attackers. According to the English the next one was just a ‘caliver shot’ or 80-100 meters beyond that, with a third less than 20 meters behind it, probably at the corner of the Carrickbroad road.

Knowing O’Neill’s methods, the first barricade may have been designed to collapse when the main English force charged it, enticing them into a killing ground with little chance of breaking through where they could be piked or shot from three sides. This is pretty much what happened on 25th September. In heavy mist an advance guard of 100 foot-soldiers made an attempt to enter the Pass, supported by three regiments. They overran one barricade, 140 yards further on they took a second, but could get no further and withdrew with difficulty and losses: a dozen dead and 30 wounded.

At least a thousand of Mountjoy’s footsoldiers would have been pikemen. The English advanced with a front rank carrying pikes 16 foot long while a second rank of taller men held 22-foot pikes over their shoulders. Their flanks were protected by a close rank of halberdiers, with musketeers further out and cavalry ranging back and forth to wherever danger presented.

This all worked well if there was room to the flankers to manoeuvre and for the pikemen to form a column 20-30 men wide. Then the enemy faced 60+ pike points coming at them at a brisk run. The English constantly complained the Irish would only fight them in ‘straitened paces’ meaning narrow passes, usually through woods more than mountains, where they were lucky to be able to march six abreast. This meant their column was stretched out, so the Irish would attack from the flank, cut off a dozen or so men and massacre them. A twenty-foot pike is not much good if a mad fella swinging an axe is coming at you from the side.

The Irish may well have outgunned the English as they had a good supply line of Spanish muskets coming in through Killybegs, and they seem to have been able to make their own gunpowder. Their muskets also had a better range than the calivers most of the English soldiers carried. The problem both sides had was rain. Almost all the muskets of the time were matchlocks: the trigger brought a burning cord or match into contact with the powder charge. The cord, hemp soaked in saltpetre, was lit at the start of the engagement and the musketeer blew it red-hot before attaching it to the trigger mechanism, then he tried to keep the burning cord dry. O’Neill’s men boasted of sudden ambushes where it was all over before the English could get their match cords lit.

England did not have a professional army: most of the soldiers were press-ganged and maybe as many as a third of Mountjoy’s men were Irish. They were a good source of intelligence and sometimes of weapons for O’Neill. The officer class was supplied by the younger sons of noble families who were not only unpaid, but often put up money to equip their company of men. They were to be paid by results in the form of land to be seized from their Irish enemies. If we look at the list of company captains at the Gap with Mountjoy, many in their 20s, we can see they later did quite well.

Blaney, Chichester, Caulfield (of Castlecaulfiedld), Hill (of Hilltown), Hill (of Hillsborough), Jerrett, Norris, Poyntz, two cousins Ross and Trevor.

Mountjoy had a close encounter on 2nd October when he went out with his staff to observe what turned out to be the fiercest engagement of the whole episode. A gentleman riding hard by him was mortally wounded. Then Sir William Godolphin, who was leading a cavalry charge during the battle ‘had his horse stricken under him stark dead with a blow on the forehead, that the blood sparkled into his face and some of the powder shot’. The English admitted that at least 55 of their men were killed in the engagement and some 105 were wounded, but they claimed that up to 400 Irish also died. Given that they were attacking over open ground while the Irish were firing from strong defensive positions, that is not mere unlikely, but impossible.

The English had some light cannon known as culverins which fired a four-pounder ball, like the one they lost a few weeks later at the foot of the Flagstaff. On 5th October Captain Blaney and some of his bravos decided to outflank the Irish by getting a gun high enough on Slievenabolea to fire down on their trenches and barricades. He led a regiment of 250 men with the cannon slung between a team of mules and another regiment in support, but it all went horribly wrong. O’Neill obviously had his main reserves up on the hillside, which was known for centuries thereafter as Eadan an Airm (Headland of the Army). The first regiment was almost surrounded and it took the second regiment to get them out with unknown but considerable losses.

There was no Geneva Convention. Wounded enemy were despatched on the ground by both sides, captured men were often beheaded. Gaelic society was even more class-structured than England and O’Neill’s horsemen were mostly sons of the aristocratic class who looked down on what they thought were low-born “English churls” who had been sent to fight them. One of their favourite tricks of psychological warfare was to race through the English camp in the middle of the night throwing the heads of captured scouts among the tents.

Mountjoy was getting nowhere fast, O’Neill was sitting pretty bcause an old ally in the war against the English had arrived on the battlefield – dysentery, which they called “the bloody Irish flux.” It had been raining for two weeks solid but the Irish were used to that. It had been very stormy and the English tents blew down night after night, even Lord Mountjoy’s own tent. Their main food was army biscuit, a sort of dry flatbread, and it was going mouldy in the barrels. Three thousand men and 800 horses had been manuring the campsite at Faughart for a month. Soon Mountjoy was losing more men to disease than to the enemy, a typical war statistic into modern times.

By 8th October with his forces wet, hungry and diseased Mountjoy had had enough and he pulled back to Dundalk. Then a strange thing happened, one that has never been satisfactorily explained. His scouts reported that all was quiet up in the Pass and when they checked, O’Neill was gone. They made their way cautiously through his barricades and down to the Three Mile Water and beyond it on what is now the Kilnasagart road, they found two more mighty barricades. Alongside the road they found a whole series of trenches where reserve troops would have been waiting to fall upon any breakthrough. On the slopes above it is still possible to find elaborate cavalry hides, horseshoe-shaped enclosures of thorn bushes and whins – originally transplanted – from where the Irish horsemen could have swept down and smashed into the exposed flank of any column that made it through. Mountjoy’s staff quickly reached the conclusion they could not have taken the Gap of the North with any acceptable level of losses, or even be sure they could have taken it all.

They set about clearing the woods by burning to ensure the Gap could not be blocked so easily again and securing the Pass with a fort. Moyra Castle was built in about three weeks in April-May 1601 under the direction of a Dutch military engineer – it could be done so fast because there was a handy source of stone in the monastery at Kilnasagart which had been closed on the orders of Henry VIII sixty years earlier. It was designed for a garrison of 12 or so but with enough loopholes to accommodate 25 musketeers, with stabling on the ground floor. Construction was done under fairly constant fire.

O’Neill’s performance in the Gap gave the place a fearsome reputation which was still alive in 1690 as William of Orange marched south from Carrickfergus. James II’s father-in-law, Louis XIV of France, had provided him with 6000 French dragoons who were eager to engage with William, whose vanguard had reached Newry although he was still in Scarva. The dragoons occupied Moyra Castle and a second very similar fort which had been built about 1624 to protect the river crossing at what is now Flurrybridge. It was known as the Water Fort. It is shown on the famous Down Survey map drawn by the Cromwellian, William Petty in 1660. All trace of this fort is gone but we can be pretty sure it was on the steep little hill behind the Carrickdale Hotel. The Williamite generals reckoned if James’s forces had faced them here, they could be in trouble:

There are reasons to believe that James’s Irish generals wanted him to fight here. To outflank the Gap from the north, William would have had to either go by the coast through Carlingford, or take a huge loop around Slieve Gullion to the north and west through what would then have been boggy and virtually roadless terrain. But his French generals thought the gentlemanly thing to do was to fight William on a big flat plain with a river running through it. There they were quickly outflanked across the bridge at Slane – which they had left open.

The first conflict between the two sides happened in Carrickarnon. On the old main road just north of the Edentubber turn at the old Customs Station there is a little narrow road on the left that runs north to Kinney’s Mill, parallel to the main road. This is the original coach road, which dips down towards the stream that marks the border. Drainage is still poor around there, but back then there was a substantial bog crossed by some sort of raised causeway, possibly with a wooden bridge. Jacobite reports said:

“Between two hundred and three hundred English foot and dragoons were coming from the Newry towards Dundalk, to know the king’s strength, and how his army lay. The Irish suffered them to pass the causeway and then they poured their shot in amongst them.”

Jacobite officer John Stevens noted in his diary: “ a party of horse under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Dempsey, advancing towards Newry, fell into a body of the enemy and, being overpowered, retreated; till coming to the above said detachment of 200 foot under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel FitzGerald and finding them receive the enemy vigorously, they rallied. The rebels made no great resistance, our foot firing hotly, but fled towards Newry, the horse pursuing them a considerable space. Of the rebels above sixty were killed, of ours a few wounded and fewer killed, among which was Lieutenant-Colonel Laurence Dempsey, shot through the shoulder whereof he died.”

(Thanks to PJ Goode, a descendant of the unfortunate Dempsey, who sent me these texts from New York some years ago.) The French lieutenant-general in command, Le Marquis de la Hoguette, wrote a report to Louis XIV’s Minister for War describing the incident.

“Ce petit avantage a fait d’autant plus de plaisir au Roy d’ Angleterre et a toutes ses troupes, que c’est la premiere curēe qu’elles ayent eu depuis cette guerre, et vous pouves compter, Monseigneur, que l’on donnera tous ses soins pour le conserver toutes les fois que nous serons obligēs d’en venir aux mains.”

William had 36,000 troops with him, which is ten times the size of the army Mountjoy had deployed in the Gap 90 years before, and sheer size brought its own problems. On the narrow road men could only walk four or five across, and given they were all carrying weapons, some room would have been necessary between the ranks. That meant the column had to be 4km long, stretching back from Moyra Castle to well beyond Flurrybridge.

There were 36 heavy cannon: each one might require six horses and they probably had at least 50 oxen which can provide much better traction in soft ground. There were 3000 cavalry and they probably had 500 or so spare horses. Armies of that size can’t live off the country. It is reckoned that a 17th-century army needed a wagon for every 15 fighting men – let’s say over 2000 wagons which need at least 4000 horses plus 500 spares. At least 10 of those wagons had to carry horseshoes and farriers. The others had to carry at least 5000 tents not to mention 20 tons of food per day. Even if we only allow 5 meters per wagon, that’s another 10 km, back to Newry Newry.

It gets worse. Armies also had camp-followers who often equalled the soldiers in number but were always at least half as many, and they had to be fed too.

The biggest group was what we would call the WAGs (wives and giralfriends), who would always have children with them – they would stretch another 2-3 km. These family camp-followers were paid to provide services such as health care, laundry and running uniform repairs, but they did not normally prepare food – there was a sort of catering corps as well as sutlers, independent providers who sold fast food to the soldiers, a cafeteria on a cart. Right at the back, and always far from the WAGs, there was a line of large, brightly coloured covered wagons and behind them walked a hundred or so women and girls. These were the hoor wagons – and in the 17th century people in England pronounced the word just as we do in South Armagh. You were probably told an army marches on its stomach. Well, now you know.

All these people were under military discipline, hoors and all, all had to be fed and protected and put up in tents that had to be carried in the wagons. The whole lot could only move at a maximum speed of about 2km an hour on the best bit of road so even if it was going well without breakdowns it would take more than a full day to pass any given point. The logistics were awful. Imagine you are the commander waiting at Kilnagsagart for reports back from scouts who are at Faughart and the vanguard at the Hip Road – how do you know what is happening to your food supplies coming through Killean, never mind the hoor wagons that are still struggling up Newry Hill? Imagine what the people of Baile an Chlair – which we now call Jonesborough – would have made of that long line making its way up the hill from the ford over the Flurry.

Eventually they all made it to the Boyne. The paintings of William show him in the thick of the action – where he would not have been – and riding a white horse, which he would not have done. White horses are relatively rare and best kept for ceremonial occasions. What you want in a battle is a nice brown horse that looks just like all the other horses. What you don’t want is all the musketeers on the other side shouting: “Get the Fxxx on the white horse.” There are also some loyalist families in the north which claim to have King William’s coat, and they probably have. Like Bruce before him, William probably changed into something a bit nondescript as he was going into battle. Through the centuries and into the War of Independence, English armies accused the Irish of deliberately picking off their officers and gentlemen rather than just butchering the common soldiers as armies were supposed to do.

What you want in a battle is a nice brown horse that looks just like all the other horses. What you don’t want is all the musketeers on the other side shouting: “Get the Fxxx on the white horse.” There are also some loyalist families in the north which claim to have King William’s coat, and they probably have. Like Bruce before him, William probably changed into something a bit nondescript as he was going into battle. Through the centuries and into the War of Independence, English armies accused the Irish of deliberately picking off their officers and gentlemen rather than just butchering the common soldiers as armies were supposed to do.

Even when the wars ended, peace did not come easily to the Gap of the North. Each war left behind bands of unreconciled fighters who took easily to semi-political highway robbery, and where better than on the hilly portion of what was still the main north-south route? After the battle of Kinsale they were known as ceithearnaigh choille,woodkerne; after the Cromwellian wars they called them tories; after the defeat at Limerick they called them rapparees – although the older term tories stuck for a long time in South Armagh. All the big names operated in the Gap: Redmond O’Hanlon, Cathal Mór Carragher and Séamus Mór MacMurphy.

The Gap of the North passed out of military history in the 1730s when the straight, wide coach road was built through Edenappa to Faughart. From 1730 there was a turnpike or toll gate at Flurrybridge. In the 1740s a new twice-a-week stagecoach service was launched from Dublin to Belfast. Sadly, on the first day of the first service it was robbed by rapparees at Flurrybridge.

Further reading:

For a brief popular account see

‘The O’Neill’ Bedevils Mountjoy at Moyry Pass

https://thewildgeese.irish/profiles/blog/show?id=6442157%3ABlogPost%3A9129&commentId=6442157%3AComment%3A223046

For more detail, Breaking the Heart of Tyrone’s Rebellion?

By James O’Neill, UCC 2017. Excellent 27-page PDF

For the serious anoraks, The State that never was:

Massive work, a 647-page thesis by Eoin O’Neill at the University of Rio de Janeiro 2005.

http://gaponorth.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Eoin20tese.pdf

The account of the battle in the Gap begins on page 498

If you can find a copy, see ‘Trench warfare in the Gap of the North, 1600’ from Cuisle na nGael (Newry, 1987)