Life is made up of connections of all kinds and from a distance they can look kind of odd – until we uncover all the little links and can see how they join together. This is me when I was very wee and living in a house called Scarce’s in Adavoyle.

Seems a previous inhabitant called McDonnell had been a bit scarce of hair. This is a goat from one of the herds wandering Slieve Gullion (photo by Marie McCartan). So far the connections might seem a bit obvious. But there is a third leg on this story: Baroness Angela Georgina Burdett Coutts (1814-1906).

She was called the richest heiress in Victorian Britain, inheriting several fortunes which from a young age she spent on a variety of good causes, including Irish famine relief. She was an acquaintance of Queen Victoria and a close friend of Charles Dickens, who dubbed her “Queen of the Poor”. She once proposed marriage to the much older Duke of Wellington but he turned her down, possibly because she terrified him. Among her causes, the Baroness put up the money for Florence Nightingale’s work in the Crimean War. Luckily, she decided to spend some of her loot on a scheme of her own devising, to provide milking goats to the rural poor of England, which indirectly benefitted some of my ancestors.

But back to me. My academic career began in 1954 when I walked more than a mile from Adavoyle with my three big sisters to

Dromintee primary school. Along the road we often met Stephen Corney leading his big plough horse on a halter. Up the hill Jemmy Ned would be putting out the cattle. Retired schoolmaster Johnny Buck or his neighbour Owney Thomas would be coming from the Post Office with their pension. We saw Dinny Oiney the holy man who came from the back end of Cloughinnea on his bike for early Mass; and sometimes we got sweets in Paddy Nicholas’s shop by the chapel. I was quite a bit older when I realised that, like me, these people were all called Murphy and the nicknames were used to tell us apart.

The nicknames are mostly patronymics, references to a common ancestor. We are the Corney Murphys, descendants of Cornelius (1806-1896) and he was the man who first got us into the goat trade. That’s why some of the other children had a wee rhyme about us: “Corney, Corney, buck of the town, one leg up and the other down”. I have no idea what it means or how it came about and those are the only two lines I know.

But I have a good idea of its origins because there is one simple, outstanding fact about South Armagh: the people who live here have not lived off the land alone for hundreds of years. The place is wildly over-populated compared to the productive capacity of the land. In the days of the landlords the British Parliament, largely made up of landlords, was for ever holding inquiries and commissions into the landholding system in Ireland.

In 1844, just before the Great Famine, Fr Michael Lennon, parish priest of Creggan and a Cullyhanna man, gave evidence to a parliamentary inquiry, the Devon Commission. He was asked how many large or commercial farms there were and he had to explain slowly and carefully that there were none. In his parish and the adjoining KIlleavy parish (then including Dromintee and Forkhill) most so-called farms were less than five acres:

“It is not by farming the people live, but by dealing. They look upon their holdings or little farms as rather a lodging or resting place and they pay rent chiefly by dealing. They go to England to labour, and many of them purchase various articles and go through the country with them, such as oranges and lemons etc.; others buy pigs, cattle and so on and exchange goods in various ways.”

So there you have it: this is the start of the origins of the dealin’ men from Crossmaglen, the pahvees of Dromintee and Killeavy and the cadgers of Omeath and Cooley, all the pedlars and hucksters and hawkers and jobbers and packmen who paid the rent on the farms so we would not starve. There were others words like ‘monger‘, which may be the origin of the Irish word ‘mangaire‘. Some of these trades are almost unimaginable today. Ragpicking may sound like an unpromising business, but in the 19th century paper was made from recycled cloth fibres. We were raised on stories of men who left Slieve Gullion with a bag to gather rags and came home a few short years later to buy a farm or a pub. One family from high on Slieve Gullion’s slopes went to the ragpicking and two generations later they had a helicopter and a new type of nickname: the Millionaire Murphys

Let us begin with migrant labour. An estimate from the 1841 census said there were at least 60,000 Irish people working on the harvest in England. Quite a few would have been women or girls.

This sketch of spalpeens (spailpíní = harvest workers) from Connacht heading for the ports is from before the Famine (note the men have boots and the women are barefoot). The main event was the wheat crop in places like East Anglia, Norfolk and Lincolnshire, but some would go off in May to do the hay in the West Country, then go east for the wheat in August-September and up in Scotland picking spuds in October.

Just think of the time it would take to walk from Ddromintee to East Anglia to work on the wheat harvest, and walk home again. Time to figure out other and maybe easier ways to make a shilling. Most of their earnings came home to pay rent on the farms, but some was invested in goods for re-sale, at home or on the way back.

Mid-Victorian police reports from northern England and Lowland Scotland refer constantly to the many Irish dealers. In Greenock, “the Irish deal in old things of all descriptions, bones, old tools, old clothes; hawkers of earthenware fish, oysters, salted meat and eggs.” In Kilmarnock, “a great number of Irish hawkers constantly in the town, dealing in drapery goods, braces, currycombs, spectacles, brass candlesticks and small articles of hardware.” In Manchester, “the Irish are gradually getting possession of the Manchester market.”

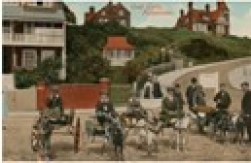

Back to the Baroness. Even as a young woman Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts had a strong social conscience. She was annoyed with the little goat carriages she saw on Victorian beaches; she thought it was shocking they were being used to give rides to the children of the rich instead of food to the children of the poor. When she inherited a huge fortune she helped establish the British Goat Society “to extend and encourage the keeping of goats by cottagers and others who cannot afford a cow with a view to increase the supply and consumption of milk in rural districts …”

According to Ray Werner of the Old Irish Goat Society, the English took such a dim view of the goat and all its works that there was a shortage of the beasts. In 1875 the British Goat Society decided to import from Ireland where there were at least a quarter of a million goats. There is no way of knowing whether this was the beginning of the export trade but it was at least the cause of a great expansion. It seems the Society was selling its milking goats to rural cottagers at 30 shillings apiece, and that would have been a significant sum back in Dromintee.

At a talk in Tí Chulainn in 2017, Ray Werner said goat exports quickly fell under the control of people from around Slieve Gullion. The goats came from the West Coast for sale at fairs in Crossmaglen, Newtownhamilton and Forkhill and were gathered into larger herds on the mountain for the drovers to take to England or Scotland.

” … it is recorded that 900 Old Irish goats were exported over a three week period in 1880. …..we have a record also of a travelling herd comprising 600 animals that left Belfast on the mail steamer in July, 1887, and which made its way to the Orkney Islands. It is therefore all too likely that 900 goats leaving Ireland in three weeks wouldn’t be that unusual. Thus, between March and August of any year, upwards of 7,800 goats would have left Ireland.

“One such travelling herd that was landed in Wales, then driven through Cardigan and onwards through southern England to Kent in the Autumn of 1891. There were 300 goats in all, these being controlled by 3 men, 3 boys and 5 dogs.”

This picture, from Wiltshire in 1889, shows a well-shod and clothed drover who could well be from Dromintee : he could be a Corney Murphy.

The goats are resting calmly on the square in Dorking, Surrey in 1897. The logistics are staggering: Dorking is more than 750 miles from Dromintee so a return journey was equivalent to three times the Camino de Santiago for which sensible people allot five weeks. Presumably the goats would mainly feed on the Long Acre – which would slow the pace considerably – but some sort of corralling with forage would have been necessary at night in urban areas. Men, boys and dogs had to be fed a few times a day and although the herds moved in late spring and early summer, some sort of occasional human shelter must have been arranged. All this could only have been financed by the sale of cattle from the wee farm at home.

Up to the outbreak of World War One in 1914, the arrival of the Irish goat drovers in English towns was a sign that spring was here. They sold milk and nannies along the way and attracted attention in the town squares by what commentators called “Hibernian blarney”, shouting about their wares and making all sorts of claims for the benefits of goat milk and meat. They would hold a nanny over their heads by the legs and squirt great jets of milk across the street, catching it in a bucket. My father told me that his father, Francie Murphy who was born in 1885, went with the goats to Glasgow as a ten-year-old, sleeping among the herd at night for heat. In Belfast, Sandy Row was the only permitted route for driving livestock to the docks and the locals often tried to scatter the goats in hopes of free meat. A couple of the older goatmen would go down first and strike a deal with the local gang boss, like paying the motorway toll: a couple of kids could buy safe passage for the herd.

Another Dromintee man, the folklorist Michael J. Murphy,did his first radio broadcast in 1937 about the goatmen of Dromintee:

He was talking about my great-uncle Paddy, who later lived near Silverbridge in Legmoylin. Paddy and several of his brothers made the epic transition from goat sales to pahveeing, selling of “suit-lengths” of serge and worsted cloth in isolated parts of the world.

We can’t be sure where the word pahvee came from – it has been claimed as a Romany word and has recently reappeared in Pavee Point, the Dublin centre for the travelling community, although researchers are pretty sure this particular connection goes back no earlier than the 1990s. Michael J Murphy thought it might of French origin and this idea was picked up by E. Estyn Evans, Professor of Geography in Queen’sUniversity. My brother Kieran has researched it and thinks it is a Lowland Scots term for a trickster, a bit of a con-man, a smartass. Considering that so many of the goat herds moved through the Lowlands, that the Irish practically controlled the dealing trades there and the pahvees originally came home that way, it is not unlikely.

The point about pahveeing is that a small group of families in Dromintee and Killeavy/Killean made a rapid transition from small-scale dealing to shipping huge quantities of quality cloth almost world-wide for sale. My grandfather Francie married into the biggest pahvee family of all, the Kearneys of Annahaia beside Slieve Gullion Courtyard.

Paddy Kearney was known as the King of the Pahvees: he was in Australia and Tasmania perhaps as many as 20 times and across the Atlantic a dozen times, and he had his own drapery shop for a time in St Johns, Newfoundland. Francie, Paddy and Michael Murphy also operated in Canada: reels of cloth six foot high were purchased in the big “rag trade” market in Strangeways, Manchester and shipped out to Halifax, Nova Scotia. There they were divided up among various Dromintee men who headed out to some small town where the railway lines ended. Then they hired a horse and buggy and headed on out to isolated farms where suit-lengths were sold to wives who wanted their husband to look well in church on Sunday. There would be a tailor, usually Jewish, in the small town: the pahvee had already made a deal with him to offer discounts on suits made with the pahvee cloth.

In reality we know very little about these young men – and they were mostly young. They planted the crops in the spring and then headed off across the world but mostly they got home in time for the harvest. Imagine selling an animal to kit your young fella out for a six-month stint selling in Canada or Australia. Supposing he was no good at it?

When I did a talk on the pahvees in Tí Chulainn a few years back and spoke of them going to Australia and Canada, a woman told me her people – McCanns of Carrickbroad – had pahveed in Russia in the time of the Czar.

Large-scale pahveeing was the creation of two factors: cheap, good quality cloth from England’s industrial revolution, and the steamships and railways which made fast travel possible. It lasted from about 1889 until the Second World War. The pahvee bought goods cheaply at the heart of urban industrial society and re-resold them out on the isolated rural fringes. It was wiped out by two further developments: the off-the-peg ready-to-wear suit from companies such as Burtons, and mail order which was pioneered by Montgomery Ward and Sears in North America. After World War II most pahvees switched to selling woollen blankets which were in short supply since so many textile mills had been switched to war production. In its turn the blanket line was knocked out by the duvet or continental quilt.

My father Jim Murphy was a pahvee all his life and literally died a pahvee: he took a stroke beside Moyra Castle after spending the day selling in Co Meath. “A good day on the road” – tht would be an acceptable epitaph for any pahvee

His brother Peter Vincent had spent some time as a young man pahveeing with their father Francie in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Peter Vincent’s son Francie – Wee Francie – is almost certainly the last person to live full-time from the trade, working mostly in the highlands of Scotland, out on the periphery of society.

.

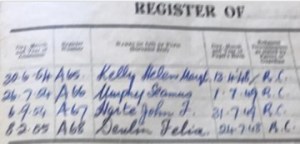

These are the other pahvee families he mentioned, most of whom spent time on the road in North America

- Skipper Boyles: Tommy, Paddy and Seamus ‘from the bog’ in Carrickbroad

- Barney McKeever, Carrickasticken

- Mickey Begley, Faugilotra

- James McManus, Jonesborough

- Peter Nugent, Dernaroy

- Owney Moore, Jonesborough

- Patsy and Tom Morgan, Edenappa

- Joe and Johnny Aiken, Jonesborough

- Tom Connolly, Faughiletra

- Larkin brothers, Adavoyle

In Clontigora, the McDonnells and the McGeoughs were pahvees.

But let us give the last word to the Baroness, who focused much of her good works on Ireland in her later years. I will never be able to see a goat on the mountain again without thinking of her